Whenever there’s a major breakthrough in innovation in Unlimited Hydroplane racing, there are always those teams who are slow to adapt to the change. More often than not, these slow adapters are small budget teams forced to race with outdated equipment and meet with little or no success on the water. With this in mind, it comes as a surprise that this trend did not begin with the introduction of Allison and Rolls Royce Merlin engine powered modern hydroplanes into hydroplane racing, not right away at least. The Gold Cuppers built years before the Unlimiteds that were on the water at the same time, more than held their own against the Unlimiteds at the time. Although major race wins such as the Gold Cup often went to modern Unlimited Hydroplanes during this era, a boat with a “G” designation was always there and won at least one race every year but one between 1946 and 1955.

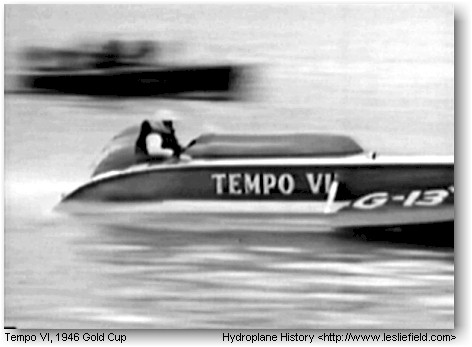

On paper, the Unlimited Class was officially born in 1946 when the cubic inch piston limitation, along with most restrictions on the length, width, and weight of a boat, were abandoned in order to take advantage of the newly available aircraft engines from fighter planes used during World War II. Despite the new unrestrictive rules, however, there was not a wealth of new boats using the new power sources right away. In fact, only two boats in the 1946 Gold Cup used these modern power sources: the Miss Windsor, a Merlin powered craft that was unable to start a heat in the race, and the Miss Great Lakes, an Allison powered craft which made a strong showing for the Allison’s debut in powerboat racing. For the first two heats, the Miss Great Lakes finished second behind the Tempo VI, then in the third heat the Great Lakes jumped out to a big lead before blowing its engine and allowing the Tempo VI to win the heat en route to a Gold Cup victory. The Tempo VI was a boat that was definitely a representative of the sport’s pre-World War II era. The boat was actually the former “My Sin” which had previously won the 1940 and 1941 Gold Cup races but was renamed Tempo VI after being bought by famed bandleader and inboard racing veteran Guy Lombardo. Despite the new name and owner, the Tempo kept the same setup as it had while racing as the My Sin along with its Miller engine. So while the Miss Great Lakes grabbed headlines with its record breaking speeds on that first national race after the end of World War II, the winner on the day was a pre-War relic and a sign that the Gold Cuppers could hold their own against modern engines.

Guy Lombardo driving the Tempo VI to victory in the 1946 Gold Cup. Photo taken from the web

1947 saw the birth of the national tour, although Hydroplane racing was still very much a regional sport and would continue to be so for the next decade or so. Once again, however, much of the attention and most of the trophies were grabbed by a pre-World War II boat. The Dossin-owned entry, built in 1939 and ran previously as the So Long, underwent a major conversion previous to 1947. The boat was converted to Allison power and changed its name to Miss Peps V. The new name represented something else new in hydroplane racing at that time: sponsorship. The boat became something of a representation of the transitions happening around hydroplane racing at the time, the boat being a Gold Cupper that converted to a modern power source and taking advantage of the new rules put in place for the Unlimited Class. Carrying the Pepsi colors, the Miss Peps V won five of the seven races it entered that year, including the Gold Cup at Jamaica Bay. Other races that year were won by the Tempo VI and the Notre Dame, meaning that seven of the nine official Unlimited races were won by pre-World War II Gold Cuppers that year. Despite this, it should be noted that most of the boats carrying “G” designations were taking advantage of the rules of the Unlimited class and were using Allison or Merlin powerplants, so they weren’t pure “Gold Cuppers” as was understood in the pre-World War II era. The following years would see more of these boats carrying “G” designations while using modern powerplants find more success in Unlimited Hydroplane racing.

1948 saw the first boats to officially carry the “U” designation into Unlimited hydroplane competition. It also was the beginning of a string of years that were unique at the top level of hydroplane racing. From 1948 through 1953, separate championships were awarded for the Gold Cup class and the Unlimited class although they competed at races simultaneously, much in the same way that separate offshore classes will often be on the water at the same time at races in the modern era. Three Unlimiteds (along with one pre-World War II boat carrying a U designation, the Hi Barbaree) made their debut in 1948, but only one managed to score any points that year. The Jack Schafer owned U-1 Such Crust finished second and won the first major race for the newly-christened U-Boats, capturing the 1948 President’s Cup to go along with a second place finish in the Gold Cup that year. The year, however, belonged to the Gold Cuppers once again. Compared to the lone points scorer for the Unlimiteds, a fleet of twelve Gold Cuppers scored points in at least one race in 1948, including Allison powered Miss Great Lakes winning the Gold Cup after just falling short the previous two years. This would prove to be the last Gold Cup win for a "Gold Cupper" hydroplane. The G-13 Tempo VI won the Detroit Memorial regatta en route the overall National Championship for the season.

A Monel Metal advertisement featuring the 1948 Gold Cup Champion the G-4 Miss Great Lakes. Photo taken from the web.

1949 once again saw the “split” format used in awarding a Gold Cupper class champion and an Unlimited class champion, but after only one season the tide had definitely turned in favor of Unlimiteds. Compared to the previous year when only one Unlimited managed to score championship points, ten Unlimited Hydroplanes scored points in 1949. Most dominant among the Unlimiteds was the My Sweetie. Piloted by the legendary Bill Cantrell, the My Sweetie won the APBA Gold Cup and five other races en route to the National Championship. As for the Gold Cuppers, the field had dwindled to six point scorers after a string of strong seasons. The G-boats still made their presence felt, however. The G-60 Lahala, a New Jersey based Allison powered boat driven by Harry Lynn, won the New Jersey Governor’s Cup and the Cambridge Gold Cup, the latter being the second time the Lahala captured the race in a venue better known for rowing regattas. Once again, however, Guy Lombardo’s Tempo VI was the class of the Gold Cupper field. The eleven year old hull won in Baltimore and was a consistent finisher throughout the season to capture the national championship.

The G-13 Tempo VI, shown here many years later after it was preserved by H.A.R.M. Photo taken from the web

1950 signaled the beginning of the end on a number of levels for the Gold Cuppers. Only four G-Boats competed this year, with three of those four scoring any points. Furthermore, this year saw the debut of the revolutionary propriding Slo-Mo-Shun IV designed by Ted Jones. The impact this hull had on hydroplane racing cannot be overstated and has been covered by a number of hydroplane writers through the years, but for the purposes of this article the focus should be on how quickly the craft made every hydroplane built before it obsolete. In scoring a dominant victory at the 1950 Gold Cup (which was still the only true national race at that point), the Slo-Mo-Shun IV deemed even Unlimiteds built a year or two before as obsolete, so it was no secret that the tail dragging pre-World War II hydroplanes’ days were numbered. Despite the changing times, the Tempo VI once again had a solid season. Guy Lombardo’s entry won four races on the year, including the National Sweepstakes Regatta and the Red Bank Gold Cup (both in Red Bank, New Jersey), the Buffalo Launch Club Regatta, and a repeat win at the Star Spangled Banner race in Baltimore. The Canadian-American’s Freeport, New York based entry would continue to be one of the most prominent boats on East Coast races for the following years.

1951 saw an increase in Gold Cupper entries compared to previous years. One of the best performances of the year by a G-Boat was turned in by Bill Cantrell driving Horace Dodge’s Hornet entry at the Seattle APBA Gold Cup. The former “Why Worry” finished second in two heats and finished an overall second on the day, finishing second in the first two heats to the Slo-Mo-Shun V. The Hornet went dead in the water during the third and final heat, but that heat was stopped after the tragic accident involving the Quicksilver which resulted in the loss of life to driver Orth Mathiot and riding mechanic Tom Whitaker, another Gold Cup boat which made its debut in 1951 but was built in a style that was more representative of the pre-World War II era. The Hornet would go on to finish third in the President’s Cup race and finish third overall in the National High Points as well as the championship for the Gold Cup Class. The only race won by a Gold Cupper that year was once again Guy Lombardo in the Tempo VI at the National Sweepstakes Regatta in Red Bank.

Two generations of hydroplane design competing side by side. The G-31 Hornet is in the background and the U-37 Slo-Mo-Shun V is in the foreground. Photo taken from the web.

Four Gold Cuppers scored points in 1952. The Such Crust IV, a new boat from the Jack Schafer camp, won the Steel Cup in Pittsburgh with Bill Cantrell at the wheel. At the APBA Gold Cup in Seattle, the G-2 Hurricane IV finished second in the first heat and failed to finish the last two heats, but that was good enough for an overall third in one of the strangest Gold Cup races in history that saw only one boat (overall winner Slo-Mo-Shun IV) finish the last two heats. The Dee Jay V, a Ventor style hull on again off again competitor since its 1950 debut, had an adventurous day at the Imperial Gold Cup in New Martinsville, West Virginia. In the first heat the G-66 Dee Jay V drove to an easy victory over the 7-litre Mercury driven by Oliver Elam after the Miss Pepsi went dead in the water. In the second heat, the Dee Jay V caught fire but amazingly driver (and boat designer) Norman Lauterbach continued to drive a few laps until finally being flagged off the course by boat owner Daniel Murphy. Despite being outscored by the 7-litre hydro Mercury, the Dee Jay V was awarded the “win” as account of being the only Unlimited class boat to score points on the day. The race would prove to be the last for the colorful boat. The G-31 Hornet-Such Crust, driven by Lou Faegol, finished first in the first heat en route to an overall second at the Detroit Silver Cup and finished all three heats in fourth place to place fourth overall at the President’s Cup Regatta in Washington, DC. Despite these being the only two races the Hornet-Crust boat entered, it proved to be enough to capture the Gold Cup Class championship for the boat in 1952. Of course, this was indicative of how hydroplane racing was conducted at the time. Consider that overall High Point champion Miss Pepsi only entered five of the twelve races in 1952.

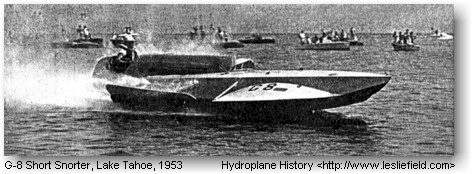

1953 saw the Gold Cuppers take home three more first place trophies. The G-8 Short Snorter, a boat that made its debut in 1939 driven by Stan Dollar, entered only two races on the season but made them count. First the boat won the Lake Tahoe Regatta then won the Mapes Mile High Gold Cup, also held on Lake Tahoe. The Tempo VI returned to competition and was once again a winner in Red Bank, capturing the Red Bank Gold Cup. The G-22 Such Crust III, another Jack Schafer entry driven by Chuck Thompson, was the only G-Boat to enter the Gold Cup that year and finished an overall third. The Such Crust III went on to finish second in the Silver Cup in Detroit and the President’s Cup in Washington, DC to win the Gold Cup class championship. This would prove to be the third straight year when the Gold Cupper championship was won by a boat that did not win a race on the year (despite the fact that multiple races were won by other G-Boats all three of those years), and it would also be the last year that the APBA would award a separate championship for the Gold Cup class. With the Unlimited sport inching toward becoming a more professional endeavor and the loss of their championship; it was only a matter of time before the Gold Cuppers, more representative of the amateur past of the sport, would be a thing of the past. Despite the slowly dwindling number of G-Boats, a few entries would soldier on for the next few years.

The G-8 Short Snorter en route to victory in the 1953 Mapes Mile High Gold Cup. Photo taken from the web.

Seventeen boats scored points in 1954, but only two of those boats carried the old “G” designation. The Short Snorter once again entered the two Lake Tahoe races, but this time had to settle for second and third place finishes. Also competing in the Mapes-Mile High Gold Cup was the Hurricane IV, who finished second in the only race it qualified for that year. For the first time in post-World War II racing, no Gold Cupper boat won a top level hydroplane race and no Gold Cupper competed in the APBA Gold Cup.

After the cancellation of the Gold Cup class championship in 1953 and the G-Boats failed to make much of a showing in 1954, it perhaps looked as if the Gold Cuppers were dead. In 1955, however a new G-Boat debuted and had perhaps the best season ever by a Gold Cupper in the modern era. Not surprisingly, it was the owner and the team that was the most successful G-Boat over the past decade. Guy Lombardo came out of semi-retirement in 1955 and debuted a new hull, the G-13 Tempo VII. The boat was still built within the pre-World War II specifications to qualify as a “G” boat although it did use Allison power. After an inauspicious beginning where the boat only entered two of the season’s first five races, one of which was the Gold Cup race in Detroit where the boat failed to finish a heat and saw driver Danny Foster suffer injuries, the boat went on one of the most memorable streaks of the 1950’s. Danny Foster returned to the cockpit and went on a tear where the boat won five consecutive races it entered: The Copper Cup in Molson, Montana, the Silver Cup in Detroit, the President’s Cup in Washington, DC, and the Governor’s Cup in Madison which would give the Tempo VII the distinction of winning the most races in 1955. The President’s Cup Regatta, then considered second in prestige only to the Gold Cup, saw the Tempo VII make an incredible come from behind victory. Going into the Final Heat the Tempo VII was fourth in points and 231 points behind the Miss Pepsi that had won its previous two heats. In the third and final heat, however, everything went the Tempo’s way as the Miss Pepsi went dead in the water and the Tempo VII went on to victory and the right to meet President Dwight Eisenhower. After winning in Elizabeth City, the Tempo VII won the Governor’s Cup in Madison, which at that time was in only its second year as a National Unlimited Hydroplane tour race but became a representation of the changing times: this would prove to be the last victory in the Unlimited Class for a boat carrying a “G” designation. Despite the Tempo’s incredible run, its late start probably prevented any chance of the boat capturing the National High Point championship for 1955 and Lombardo, Foster, and the Tempo VII team had to settle for second in the High Points behind the U-55 Gale V. It should be noted however, that the Tempo VII finished ahead of the Gale V on a routine basis in 1955 and the Gale V entered and finished on the podium in all five races that the Tempo VII won. Despite its late start, Lombardo’s Tempo VII was definitely the boat to beat in 1955.

Almost to prove that the Tempo VII’s success wasn’t a fluke, another Gold Cupper, the G-22 Such Crust III also had a stellar season in 1955 and won the St. Clair International Boundary race.

Unfortunately, neither the Tempo VII nor the Such Crust III was able to repeat their success in 1956. The Tempo VII entered the season opening Maple Leaf Trophy race in Windsor, Ontario, but sustained damage and was unable to start a heat. The only other race it entered was the season’s penultimate race: the Governor’s Cup in Madison where the boat finished fourth. The Such Crust III found itself plagued with mechanical difficulties throughout the season and saw its best finish as a third place (in a field of four) at the St. Clair International Boundary race. The hydroplane racing world around them was also changing. By 1956, many of the top flight teams were converting from Allison engines to the more powerful Rolls Royce Merlin engines and within a few years it became no secret that a team would need a Merlin engine if it expected any type of long term success (although a handful of teams used Allison power throughout the thunderboat era of Unlimited racing). The Gold Cup boats, already considered by many to be too small to carry an Allison engine, was way too small to handle the horsepower of the Merlin and an already dying design option became completely obsolete. Also, the sport was becoming more professional with the formation of the Unlimited Racing Commission in 1957. The Gold Cuppers, more representative of the sport’s amateur days of being an expensive and adventurous hobby for those who had the means and the will to throw a lot of money around, found themselves as a square peg in the round hull of the newly professionalized Unlimited sport. So when the Unlimited Racing Commission had its first season in 1957, the Gold Cuppers were left in the past. A decade after the new relaxed rules and the creation of the Unlimited class planned their obsolescence, the Gold Cuppers were finally no more. It should be noted, however, that the two remaining G-Boats did compete for a few more years as U-Boats. The Such Crust III continued for three years under the same name as the U-60 and the Tempo VII was sold, the name changed to the U-99 Miss Detroit, and had a couple of stellar seasons topped off by a 1960 President’s Cup victory.

After 1956, the G designation was no more in the Unlimited Class. Every now and then over the last few decades there is talk of recreating the “G” Class as a step down from the Unlimiteds on the hydroplane ladder or perhaps as a substitute for the Unlimiteds by some ambitious souls. Most notably, during the back and forth between the two competing Unlimited sanctioning bodies in 2004, both the Hydro-Prop and the Unlimited Lights (who had sanctioned the “outlaw” Unlimited races that year) leadership claimed to have tentative plans of creating a G Class. Currently there are a handful of boats carrying this designation, but they are a few and the sanctioning North American Challenge Cup Series has never really gotten off the ground. It has been more than a half a century now since the last time a G-boat competed alongside the Unlimiteds, and really their story has never been told. It was not uncommon for over twenty Unlimiteds to compete over the course of the season in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, so the loss of a couple boats built to obsolete specifications was hardly remised during this era. The accomplishments of the boats owned by Guy Lombardo, Jack Schafer, and the other G-Boats, however, show that even when facing the new innovative boats these smaller hulls could still compete and grab its share of victories.

My thanks to Jim Sharkey’s “Hydros Who’s Who,” Leslie Field’s Hydroplane History website, and various articles by Fred Farley available through the Hydroplane and Raceboat Museum for the information provided for this post.

No comments:

Post a Comment